Welcome to Pocketful of Prose, a community for sharing stories. As always links are in bold, and there’s an audio of this pocket if that works better for your life. If you like it here, you can support my work by clicking the heart at the bottom, restacking this post, or sharing it with a friend. Pocketful of Prose is free for everyone, but you can support my writing by becoming a paid subscriber.

Without further ado, today’s pocket.

This week Sarah Inama, an Idaho sixth grade teacher, was instructed to remove a sign from her classroom that said, “Everyone is Welcome Here.” Her district informed her that in the current political climate, her sign constituted an opinion and violated district policy.

I work as a classroom teacher and an instructional coach in Spokane, Washington. In one of my coaching cycles, a fellow teacher and I spend a lot of time strategizing about one student. She has several students in her class who have special needs, and this student is autistic. He is a super sharp, capable student, but he doesn’t always want to read. He is a strong reader, and he often has a book on hand, but when she asks him to take out his textbook, he puts his head down or reads his own book instead. His teacher doesn’t want him to opt out of learning the material, so she is always brainstorming how to support him. This teacher often has 99% engagement in her class, which is incredible, but she wants to create an inclusive community where everyone participates.

This is what we mean when we say everyone is welcome here.

Her dedication caused me to reflect on my own first period class. 99% of my students socialize and connect with other students in the class. 99% of the students have a sense of belonging, which is excellent, for everyone except the one percent whose name is Jack. Jack will do the classwork when prompted, and he works just enough to pass my class. It took several weeks of me checking in with him, but he eventually started talking to me. For example, I know that he got new tattoos this year, and that he was worried that his girlfriend would dump him, and that his worries turned out to be true. Jack doesn’t share any of this with the other students though. I can only get him to share with the students sitting next to him by prompting him, and even then, it’s just a short, barely audible response to the subject at hand.

We have a group project coming up, and so I contacted Jack’s parents and asked for their support. I want him to collaborate with other kids in the class. Jack’s parents agreed to help me. I chose a group to place Jack in, a kind group of boys who had some resistance at first but are now hopeful that Jack will start to loosen up around them, that he will feel more comfortable. “That’s how it was with one of our friends,” one of the boys told me. “He was so shy at first.”

This is what we mean when we say everyone is welcome here.

With two colleagues and friends, I created our school’s equity team, a group of teachers and students dedicated to making sure that all students feel safe in our building. We meet regularly to discuss student voice, staff development around issues of equity and ways that we can enrich the curriculum with diverse material. We advocate for students where we can. We designed shirts for our team that say, “Welcome Diversity, Choose Kindness, Show Empathy.” On the back, the word safe is outlined, and within that outline, safe is written in over thirty languages, all languages that are spoken by students in our building. Our T-shirts remind me of Sarah’s sign, and I wonder what it would feel like to be told that we could no longer wear them. It would never occur to me that such a thing would ever be asked. Wanting to keep students safe is not an opinion, any more than wanting students to be welcome is, regardless of the political climate.

All parents want their children to be safe and welcomed.

Yesterday, I wore my equity shirt to our school’s multi-cultural celebration. During the day, we had a con in the gym, which started with a fashion show where students carried their country’s flags and wore traditional dress representative of their culture. It was a parade of color and joy and the whole time that students circled the gym, I thought about Sarah’s sign, her classroom and her school and about all they were missing out on.

In “The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” Audre Lorde wrote “we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change. Without community there is no liberation, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between an individual and her oppression. But community must not mean a shedding of our differences, nor the pathetic pretense that these differences do not exist…It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths.” So much strength in this room, I thought, as our students proudly displayed their cultures, and the rest of their community cheered for them.

This is what we mean when we say everyone is welcome here.

In the evening, we had a celebration in our school commons catered by Feast World Kitchen, a non-profit restaurant which empowers immigrants and former refugees. There were performances by the Spokane Chinese Organization, which included fan dances and a dragon dance. One of our Native students performed a jingle dance, a traditional Native American healing dance. Another one of our students, the president of our school and a member of both our school’s multi-cultural club and our Native Student Union, read a poem he wrote. Spokane Taiko brought their drums. There was Congolese and Pacific Islander dancing. One student from another school performed a Bollywood dance and then invited the crowd to come and learn some moves with her.

This is what we mean when we say everyone is welcome here.

My daughter, Anna, attends a different school, but I took her with me to the celebration. I would have brought my whole family, but my son had a basketball end of season dinner, and Dan was on puppy duty. Anna was excited to attend when I invited her. She knew Feast would be catering, and one of our dear family friends who we hadn’t seen in a while would be there. She was excited for the performances, but as we walked over to the school, she started to get anxious. She wouldn’t know anyone. I would know everyone. She was worried about being welcome.

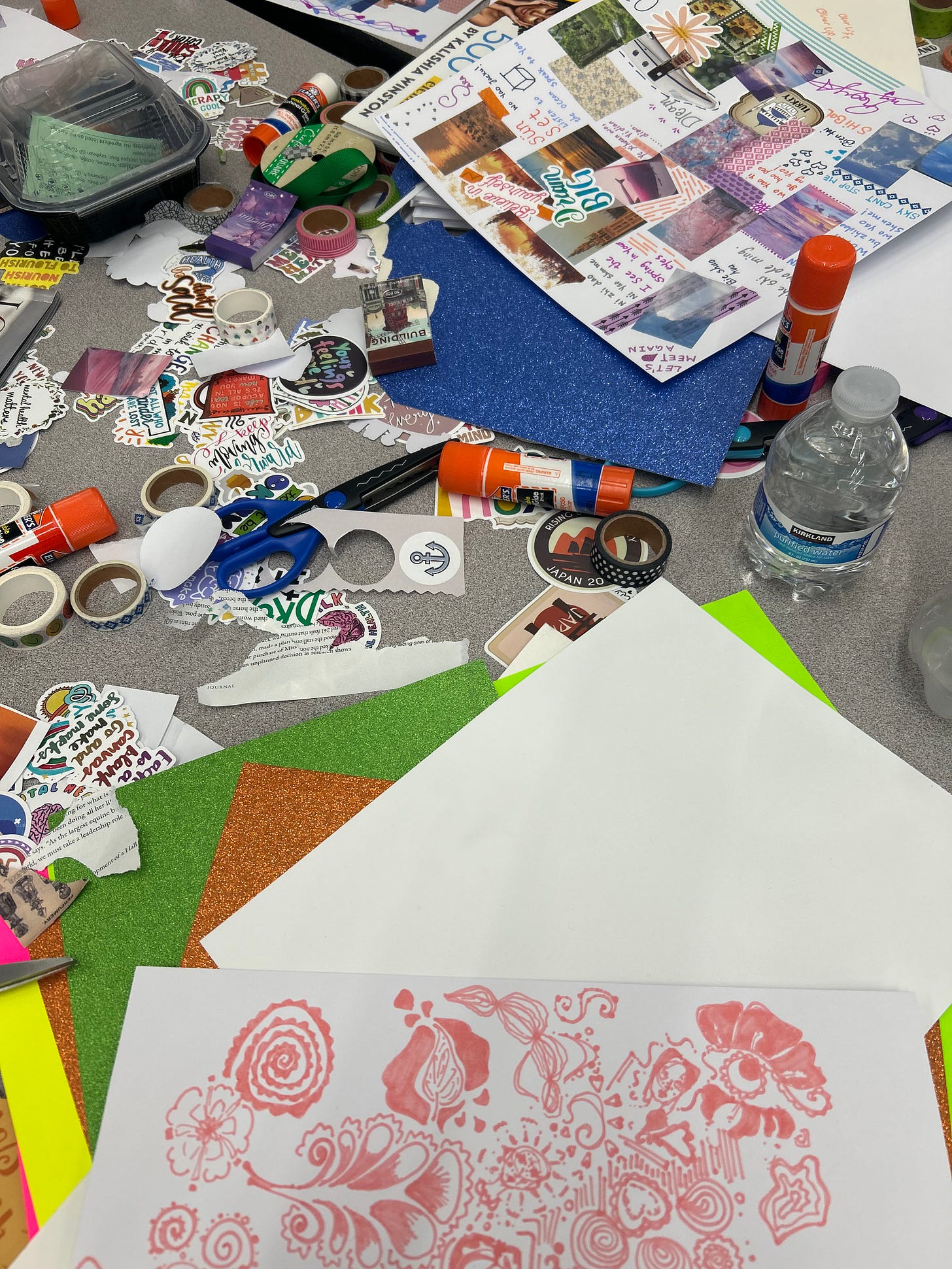

She helped me set up our multi-cultural book club table which featured books we have covered in the club, books by a diverse range of authors from James Baldwin to Angie Kim to Thomas King. It also included several other titles that our librarian had chosen to represent a myriad of voices and topics. We set up a vision board making station. Vision boards allow you to choose pieces of color, art and words that speak to you, and piece them together to affirm your identity and manifest your dreams. Vision boards allow us to find joy in who we are and to imagine the world as we would like it to be.

My friend Pingala, who lived in a refugee camp for eighteen years after being forced to flee Bhutan attended the event and hosted a table to highlight the work she currently does with refugees. She brought three Afghani teenage girls with her. She told me she wanted to introduce them to Anna, that she was planning a trip to the movies on Sunday, and she was hoping Anna would come. Pingala wanted the teenagers to feel welcome in a country where they don’t know many people, where they are still learning the language.

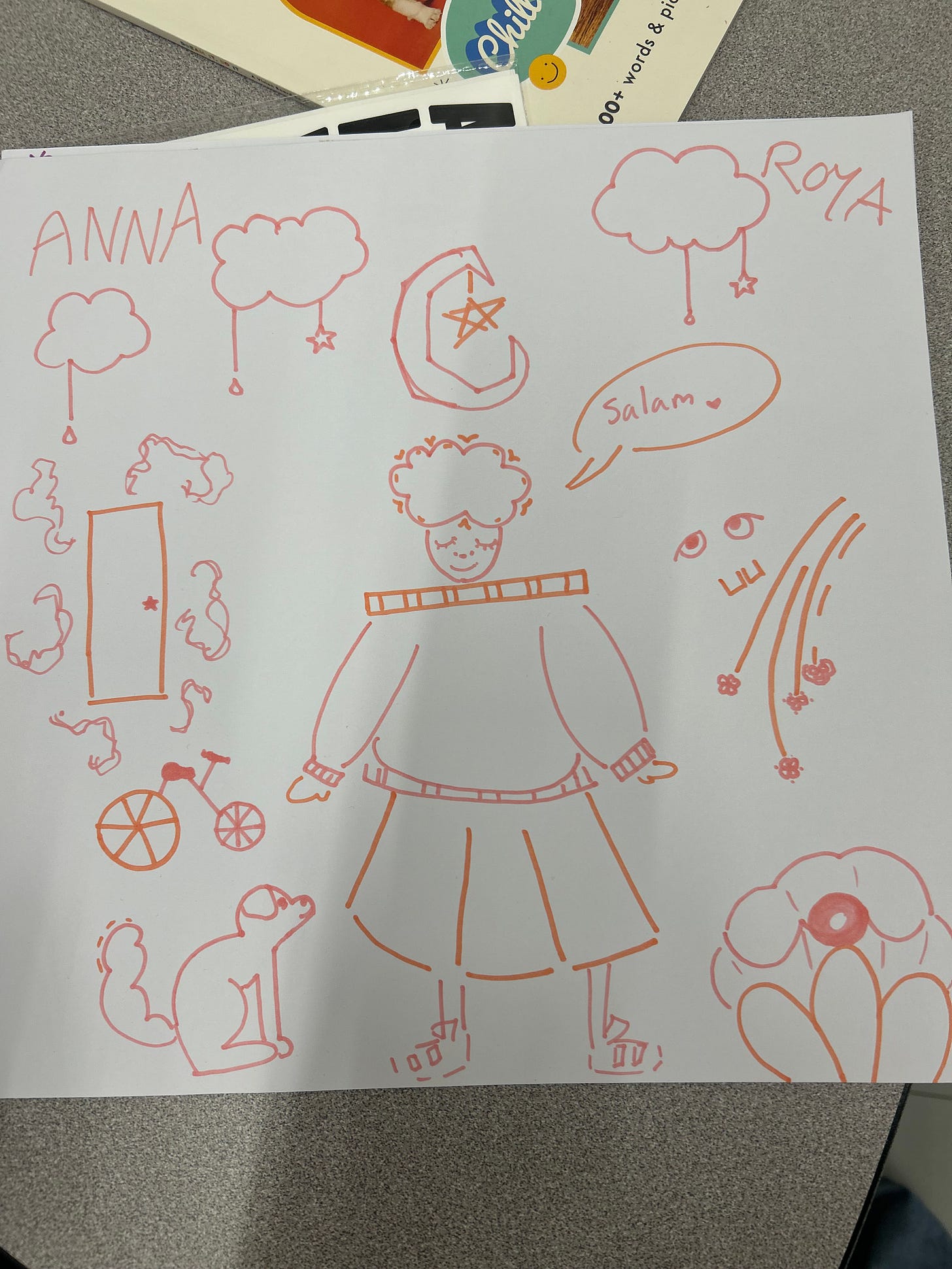

While the world around us buzzed with conversation and the deep sounds of drums, things at our table were quiet. Starting conversations with new people is hard, perhaps a little harder when there is a language barrier, but the vision board activity helped, and at some point, Anna and Roya, one of the Afghani teenagers, started drawing together. They laughed, played with a baby, whose mom visited the table, and made a plan for Sunday.

This is what we mean when we say everyone is welcome here.

As the evening came to a close, there was an invitation from the stage for the community to participate in a round dance. A round dance is a Native American friendship dance that is performed at pow-wows, where everyone is invited to participate. “We need to dance,” I told the girls. They all looked at me uncertainly, but they followed me. Most of us are just waiting for an invitation to belong.

In the gym, we formed a circle, a group of people holding hands, honoring the differences among us, united as members of a community. As the sky outside turned many colors and sunset approached, we held hands and danced in a circle, some of us having done this many times before, some of us never having done this before, most of us unsure of the next step, but laughing and looking into each other’s eyes, holding onto one another. As we made our way around the room, I kept inviting more and more people into the circle.

This is what we mean when we say everyone is welcome here.

The evening culminated with a celebration of Holi. I first learned about this celebration from Pingala. Holi is a festival of colors, a Hindu festival which celebrates Spring and the triumph of good over evil. The school provided everyone with white shirts and colored powder. We put the shirts on and headed outside. First, we placed the powder on the faces of our friends, as is custom. Then, on the count of three, everyone tossed their colors into the air. For a minute, the world was awash with color.

I wish Sarah Inama could have joined us in our celebration. I think she would have liked it. I’m comforted though by the community members that are surrounding her and holding her hand during this time, by the people who have made shirts and bracelets to show their support.

Sarah took the sign down like her district told her too, but after giving it careful consideration, she returned to her building on the weekend, with her husband and her baby, and she put the sign back up. I imagine she couldn’t stop thinking about the world she wants her child to live in.

Resistance can look like protesting, voting, boycotting, and marching, but it can also look like a sign welcoming students and a table full of stickers and washi tape. All of it matters. I’m thankful to participate in some of this work beside you and other colleagues who keep me hopeful.

Beautiful! I've always loved the atmosphere at the school, more than any other in Spokane. This work that you are doing is a big part of the reason why 💜