Welcome to Pocketful of Prose. This week’s pocket features my first brief interviews. My gratitude goes out to Eli Francovich for letting me feature him and his work in this space and to my dad, my uncle and my cousin for answering my quirky questions about my grandparents. Pocketful of Prose is free for everyone. Please share with your friends, human and canine. If you want to support this publication, you can do so by becoming a paid subscriber.

As usual, this week’s post includes an audio recording if you find that works better for your life. I tried taking the recording outside again. It worked so well with the roosters a few weeks back, but my dog Cato didn’t really cooperate, nor did the crows, or the trains. It was utter chaos, really, so I’m trying this again in the shelter of our lake cabin with Cato sleeping beside me having petered herself out, sabotaging the first two takes.

Without further ado, today’s pocket.

For the first time in a hundred years, the wolves are returning to Mount Spokane. With so many species extinct or facing extinction, this news brings me hope. I had a similar feeling last Spring when the Coeur D’Alene tribe released hundreds of Chinook salmon into the Spokane river returning them to a home they hadn’t inhabited for more than half a century. Unlike the return of the salmon, though, the return of the wolves is a bit more contentious. Let’s just say not everyone is as excited as I am. When your living depends on livestock, and those livestock are being preyed upon by wolves, it is understandable that this might dampen your enthusiasm.

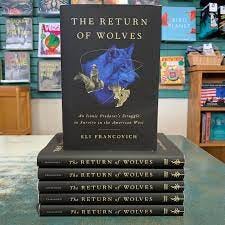

Eli Francovich, a journalist for the Spokesman Review, investigated the divide between conservationists and ranchers, and he found a real-life protagonist in Daniel Curry, an activist and range rider. Eli’s book The Return of Wolves, came out in print earlier this month.

Eli talked about his book just last week at an event hosted by Northwest Passages. On the Bing Theater stage, he was joined by Daniel Curry and Tyler Comrie, Spokesman Review photographer and reporter. Before Eli met Daniel, he was writing a lot about wolves, trying to stay neutral, but it seemed no matter what he wrote, no one was happy. When he met Daniel, he realized there might be a different way of looking at things, one that respected the concerns of both sides and posited new solutions. Daniel works in human wildlife conflict mitigation. He rides his horse Griph from dawn to dusk positioning himself and his team of three Dobermans between wolves and cattle. He is literally bridging the divide. You can learn more about Daniel’s work here.

One of the first things Daniel says on stage is that “Wolves can teach us how to be better humans.”

My hand immediately shoots up in the air.

“But how?”

I believe him, but I want the details. Daniel says that wolves can remind us that we are not in control of everything. Hmm… like audio recordings we try to make with our dog. He may have something here. Wolves teach us to look for balanced solutions to problems. They remind us that listening is more important than speaking.

In the podcast, “The One You Feed,” which coincidentally begins with a parable about two wolves, Eric Zimmer says that “it takes conscious, consistent and creative effort to make a life worth living.”

For Daniel, this effort is made in relationship with wolves. For me, it is made in relationship with writing. I wonder what this effort looks like for you.

Part of my vision in creating Pocketful of Prose was to lean into writing as a means to better living.

Perhaps, you are wondering “But how?”

How does writing lead to better living?

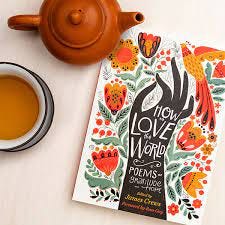

In an episode of "The One You Feed" which I have started referring to as The Good Wolf podcast, Eric interviews James Crews, poet and editor of several poetry anthologies including How to Love the World. If you haven’t treated yourself to one of James’ books, you should. When he talks with Eric, James says that our most beautiful moments in life are quick and fleeting. The gift of writing is that we are able to relive these moments again and again.

As a result of my writing practice, I find myself slowing down more in everyday life. I stop on the soccer field as I drop off my son, pausing to brush a strand of hair away from his face before he heads onto the field. I watch him run to his team, joy in each step. If you read my post last week on parenting, you know that I am not always this close to Zen, so I appreciate the gift of presence when it comes. I think writing helps me show up authentically, more often.

In writing, we not only can relive beautiful moments, but we can also remember the beautiful moments we shared with those we love who are no longer with us. I am working on a memoir about our experience fostering, and in one of the chapters, I trace a story back to my grandparents’ cellar. In trying to remember the details of the cellar, I reached out to my family, and this led to the sharing of stories about my grandparents. Born in the Depression era, my grandparents kept their fridge and freezer stocked to the brim. They had two fridges, one upstairs and one downstairs, and two freezers in the cellar. In addition, they kept the cellar shelves lined with canned goods and mason jars upon mason jars upon mason jars of homemade jam and oxtail soup. Everything was bought on sale at C-town and stored for an indefinite period of time. My cousins and I recall soda bottles advertising movies that had come out two Christmas’ before. My dad tells the story of how one time, my grandparents came on vacation with them, and they of course brought an ice chest full of food. One night, they pulled a package of hot dogs out of the ice chest, and those dogs were a very wrong shade of brown. My grandmother agreed that they probably should not cook them, but my grandfather looked at my dad and said, “So you are saying that we are going to throw these out?”

When we lose people we love, people who have formed us, our grief is vast. But in sharing stories, we bring them alive again.

Zora Neale Hurston exemplifies this best in Their Eyes Were Watching God, when Janie realizes, that Tea Cake, her late husband and the love of her life, cannot really ever leave her. “Of course he wasn’t dead. He could never be dead until she herself had finished feeling and thinking. The kiss of his memory made pictures of love and light against the wall. Here was peace. She pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes.” When I share stories with my family about family members we have lost, I feel like we are each holding a piece of the net.

Writing helps us relive our good memories, but it also helps us cope when things are hard. Some days I start my writing with the words, I am not okay because that is the truth, and as Maya Angelou says, “the page is our best witness.”

Through writing, we can work things out even when they are difficult. Dan and I were recently asked to foster again. We shared our concerns about our foster experience with the state. We were deeply hurt by the process as were the children and other families involved. While I’m not super hopeful something will come out of sharing our concerns, putting our experience down on paper helps us to process our pain.

I realized as I was working on this piece that while I asked Daniel how working with wolves led to him being a better human, I didn’t ask asked Eli if he felt writing made him a better person. I reached out to him this week to pose this question, and he kindly humored me with a generous response. Here’s what he said. “I think it can. The type of writing I love - and aspire toward - is one that puts the subject in conversation with the reader. I've found as a journalist that the process of interviewing someone helps me see the world through their perspective. That of course builds empathy, which fundamentally changes how you view the world. As a journalist I've seen tough things. Last year I traveled to Ukraine for the paper and spent a week with refugees. The grief was overwhelming. But the process of writing stories about that grief, the process of reviewing my notes and then attempting to fairly and accurately convey that via the written word, helped integrate that grief and that world view into my own life. My life is nothing like that of a Ukrainian refugee. Yet, those stories now live in me, and I hope give me more empathy and perspective.” If you want to read more about the reporting Eli did in Ukraine, you can do so here.

If writing builds more empathy and perspective, then perhaps we as writers can also learn to build bridges like Daniel is doing. There seem to be plenty of people today shouting across the divide, but I am interested in the writers, like Eli, who are encouraging conversation, suggesting that perhaps if we listen to one another, we might learn something. We might even find a way forward.

I would love to hear from you this week. What resonates with you? Where are you finding hope? What are you learning? What is the work that is making you more kind?

Because this week’s pocket mentions the return of the salmon, the war in Ukraine and the news, I’m including a poem I wrote last spring which mentions all of these things. I don’t have a poem about wolves yet, but it’s brewing.

The Journey of the Salmon

Buried beneath the news of the devastation in Ukraine

the expanding front and the looming threat of nuclear war

Hidden behind the details of another Covid variant

and more reminders that returning to normalcy is just an illusion

Shadowed by the reports of a madman targeting the unhoused

Killing them in broad daylight like rats

and the personal news of the bone marrow scan

which was not so good

is something else

a hint of light in the darkness

The Coeur D’Alene Tribe released 500 Chinook salmon into Latah Creek

and as I ran by the creek yesterday

able to run for the first time in months on my healing knee

I sifted through all the other news

like silt from the river

and let my heart rest in the waters that remained

This act of courage and quiet leadership

of change and possibility

That after eighty years of dams, destruction, and devastation

Salmon might spawn in the Columbia River again

And on their journey from creek to river to ocean

We might learn from them

Oh, Great Teacher

There is some labor that we do

Whose fruit we will never taste

We sacrifice for the next generation

and remember that this gift is only borrowed

ours to hold for a moment

The salmon are no strangers to atrocity

nor are the tribes who hold them gently in their nets above the river

I will not deafen my ears to suffering

but I won’t fill them so much that I can’t see something else

The prayer that is said at the side of the creek

The salmon that are lifted toward the sun

The eagle that flies overhead the minute they are released

The silver green scales glinting in the light

The hope we hold within

I will follow the news

but I will also follow the journey of the salmon

Beautiful piece, Mary! Thank you for sharing this with us.

I love the idea that we stay in a relationship with those who have passed through storytelling.