Welcome to pocketful of prose. If you received this from a friend, please join us by subscribing. It’s free. If you already subscribed, welcome back. If you like what you read, please click the little heart at the bottom, it warms my heart and helps people find us.

This publication is a work of heart and available to everyone for free. As John Darnielle of The Mountain Goats says, “some things you do for money, and some things you do for love, love, love.” That being said, if you would like to support this publication with your pocket change, you can do so by becoming a paid subscriber.

And now for today’s pocket.

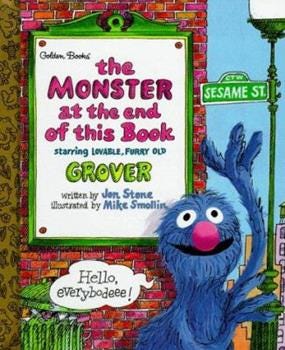

Do you remember Grover from Sesame Street, you know loveable, furry old Grover? He’s the star of Jon Stone’s, There’s a Monster at the End of this Book, which was one of my favorite books as a kid. Grover learns there will be a monster at the end of the book, and he spends most of the book begging us not to turn the page.

Grover is desperate to keep the monster out. He ties the pages of the book together with rope, nails boards, and stacks bricks all in an effort to escape coming into contact with the monster at the end of the book. Despite Grover’s desperate pleadings, we keep turning the page. At the end of the book, spoiler alert, Grover discovers that he, loveable, furry old Grover, is the monster. He feels a little silly, but he is mostly relieved. He no longer has anything to be afraid of.

(35) Grover reads The Monster at the End of This Book - YouTube

It feels fitting to me that this book was my childhood favorite. Grover’s struggle to stop the monster at all costs reminds me of my own childhood struggle. Bizarre, awful thoughts, sometimes sexual, sometimes violent, would come to me at the most random moments. I didn’t know then, what I know now about intrusive thoughts, that they are common and that they affect millions of people. They also are not a sign that you have a “secret desire to do the things that pop into your mind.” In fact, it’s rather the opposite. Childhood me didn’t know this, though. I just thought I was weird. I thought if people knew what was really going on in my head, they wouldn’t love me. These thoughts were the monster at the end of my book. Like Grover, I tried everything I could to block them out, rope, nails, bricks, but my mind kept turning the page. Unlike Grover, I wasn’t relieved to discover the Monster was me. I was terrified.

(You can learn more on intrusive thoughts here.) Managing intrusive thoughts - Harvard Health

We all have Monsters, intrusive thoughts, past traumas, inner critics, that lurk in the dark shadows of our mind, and they really fuck with us.

Natalie Goldberg calls her Monster monkey mind. Monkey mind is a Buddhist philosophy which refers to our inability to quiet our mind when there are many thoughts, ideas, and worries swirling around in our head. Monkey mind tells us that our stories don’t matter; “You are a jerk, who ever said you could write (or fill in the blank with any desire of your heart), I hate your work, you suck, I’m embarrassed, you have nothing valuable to say, and besides you can’t spell” (Writing Down the Bones Goldberg). Goldberg says the more we know Monkey mind, or the editor, as she sometimes calls him, the better we can ignore him. She advises us to let Monkey mind prattle on until he stops prattling, and to never stop writing.

Julia Cameron, author of The Artist’s Way, calls her Monster the Inner Censor. The Inner Censor is “that internal voice that tells us we are not doing well and that we could do better. Our Censor attacks us from out of the blue and its voice has a damning certainty. We could have, and should have, done better, states the Censor, and we often repeat this criticism to ourselves. In dealing with the Censor, it helps to know that its negative voice is not the voice of reason. Rather, it is a caricature villain who will always be on the attack until we stand up to it and say, “Oh— that’s just my Censor” (The Artists Way Cameron). The Inner Censor’s one goal is to prevent us from living free and creative lives.

Liz Prather, in her new book The Confidence to Write, calls her Monster a gremlin. It whispers, “not smart enough” and “not good enough.” She explains how psychologists describe shame as a master emotion. “It demeans our sense of self-worth, where our imagination, ideas, values, and opinions all stem from.” As teachers, and I imagine as parents too, we can reinforce this negative self- talk unintentionally when we present writing (again fill in the blank with most any activity) as an “exercise in correctness instead of an exercise in discovery…For many students, education is a twelve-year-long date with the critical voice” (The Confidence to Write Prather).

Alex Dobrenko, who writes the Substack Both Are True, refers to his Monster simply as Crit, “the bad guy who criticizes everything about your partner so he doesn’t have to criticize you.” The masks we wear: from expecting to accepting (act three, romcom) (substack.com) Alex’s version shows how the Monster can take different forms and shapes. Some of our monsters cause us to turn on ourselves. Some cause us to turn on the ones we love the most. Alex doesn’t give a lot of advice for how to deal with Crit. He just says maybe, “Crit can soften eventually, realizing that it’s just so much more chill and nice and good to not be a critical asshole.”

I’ve decided to call my Monster Gloria, after a girl in high school that always seemed out to get me. Gloria is a real bitch, not high school Gloria. She was probably just an insecure kid troubled by her own Monster. But my Monster Gloria, the one that lives in my head, she’s the worst. She doesn’t do anything. She just sits on a cushy throne in my mind, tapping her long press-on nails against the edge of my sanity, commenting on everything. In her kitchen, she serves only shame, and in her garden, she grows only doubt. I detest her.

And yet Natalie Goldberg says the more I know her, the better I can ignore her, which has me wondering…

Should I invite my Monster to tea?

I’m on the fence about this, so I’ve decided to consult the great thinkers. Rumi, the 13th century Sufi poet seems to say yes. Being human is a “a guest house.” He encourages us to invite all of our Monsters in and to treat them hospitably. The Guest House by Rumi | The Poetry Exchange I find some comfort in this. My experience when it comes to my intrusive thoughts is that the more I try to push them out, the more they return in full force. Somehow in allowing all my thoughts to enter my mind, even the ones I don’t really want or fully understand, I am taking power away from them. However, I have some doubts about Rumi’s approach as hospitality includes room and board. I’m just not sure I’m willing to go that far for Gloria. I don’t really want her getting her grimy hands on my grandmother’s china.

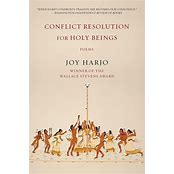

Here, I think I resonate more with Joy Harjo’s advice in Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings. In her book, Harjo shows a path to healing. This path begins with learning to listen better, but she draws the line at greedy, ravenous monsters. “Do not feed the monsters,” she writes, “They feed on your attention, and feast on your fear” (Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings Joy Harjo).

We feed the monsters every time we scroll through social media thinking other people have figured something out that we haven’t. We feed them every time we compare the cleanliness of our kitchens, the tidiness of our lawns or the compactness of our bodies. We feed them when we internalize the messages blasted to us about beauty. That it is thin, white, young. We feed them when we ban books because we are afraid of ideas. We feed them when we listen to people who claim they are attacking ideas when they are really attacking people. We feed them when we criminalize the unhoused and the addicted without taking responsibility for the conditions and systems that have made them so. We feed them when we continue to pillage our planet, our home, extracting resources without considering relationship and reciprocity.

We feed the monsters when we listen to the garbage they spew at us…that our stories don’t matter, that we are taking up too much space, that we should feel guilty and ashamed. We feed our monsters when we don’t believe that we deserve to live free, creative lives.

We feed them, but we don’t have to. We don’t have to feed the monsters.

Gloria came knocking last night. She thinks this article is shit. I invited her in and offered her some weak tea in my least favorite mug. She slurped and prattled on about how I am wasting my time on my hobbies when there is laundry that could be done. She said she was ravenously hungry, and did I have anything decent to eat? I kept writing and then politely showed her the door. Then, I helped myself to some chocolate chip espresso cookies and rewatched The Muppets take Manhattan, to remind myself, that like Grover, not all monsters are bad.

What resonates with you today? If something resonates, please tell Gloria to suck it by liking my post. I would love to continue this conversation in the comments. Tell us who your favorite monster is. If you’re feeling brave, tell us about your Monster and whether or not you’ve decided to invite them over for tea.

Thanks again for reading. Please share with anyone who you think would enjoy the read. Giant thanks to my actual editor, my daughter Anna. She has a knack for locating the light, laughter and beauty in the writing and in the world.

Really enjoyed reading! And no, your article isn’t shit. But we all shit-talk to ourselves sometimes. My monster’s been more manageable because it’s freed from secrets that shouldn’t have been kept. There are so many ways to get those secrets out. Talk therapy of course. Creative outlets help too. But I try to think of it as an ongoing process.

Also, love your use of children’s books to help frame an idea. Sharing children’s books with my kids inspired me to become a writer. It’s amazing how much they can teach using simple text. And how they perfectly capture good things, like awe, joy, and overcoming a fear of monsters.

My monster is a nervous and risk-avoidant bossy child. I think I’ll name them Little One, to diminish them. Or maybe I should hug them, and tell them we are okay now.